What follows is some really basic and essential advice that will help you create characters that leap off the page. But I’m gonna start with the caveats on this post straightaway: don’t take this advice overly literally.

I’m not saying you can’t name a universal emotion in a novel full stop. When I say “avoid,” I mean just that: try to avoid them.

This advice is a variation of the old adage “show don’t tell,” and, for my money, it’s the most important variation.

Try not to name universal emotions. Like this:

Bartholomew looked angry.

Alice felt frustrated.

Lupita seethed with resentment.

Don’t do this! Here’s why.

Why you should avoid naming universal emotions

Everyone feels angry, frustrated, and resentful at times. Humans all possess roughly the same palate of emotions. They’re universal.

But how we channel and express these universal emotions is what makes us unique. Some people react to frustration by lashing out, by laughing sarcastically, silently seething, you name it. The amount we feel certain emotions and how we react to them differentiates us and makes us individuals.

So if you’re trying to show a character reacting to something that happens in the novel, if you just tell us “Alice is frustrated,” it doesn’t tell us anything unique about Alice and doesn’t make her feel like an interesting individual. Chances are the reader has already deduced that Alice is probably frustrated from the chain of events anyway.

Show us how Alice acts when Alice is frustrated. Let the reader infer her emotion from the context and her actions. Let us see what she does when she’s frustrated. We’ll learn far more about her as a character and she’ll seem more vivid.

Here’s how to do that.

How to show emotions

You have three basic options for showing emotions: you can use a gesture, you can use dialogue, or, for anchoring characters in first person or third person limited or with an omniscient voice, you can weave the emotion into the narrative voice and show the reader the character’s thought processes.

So for instance, let’s say your original sentence was “When she heard the news, Alice felt frustrated.”

If you’re using a gesture, you can write something like:

When she heard the news, Alice intentionally kicked her toe on the curb.

If you’re using dialogue, you can write something like:

When she heard the news, Alice shouted, “Well that’s a load of balls!”

If you’re weaving the emotion in the narrative voice, you can write something like:

When she heard the news, Alice immediately blamed the coach. Honestly, who thought letting a nineteen-year-old take the fifth penalty kick was a good idea?

Each of these latter three approaches feels far more vivid than a flat and diagnostic phrase like “Alice felt frustrated.”

Spice up your reactions, dialogue, and thought processes

If you want to take this a step further, as you transition away from naming universal emotions, try also to make sure you’re showing unique reactions, dialogue, and thought processes.

Notice in the examples above, I didn’t simply show Alice sighing, saying “Ugh!”, or calling it frustration by another name. Instead, Alice acts more uniquely than that.

Try not to use more than two generic gestures like sighs or eye rolls in the whole novel, spice up your dialogue, and channel a vivid and individualized voice when you’re showing a character’s thought processes.

Especially as you’re revising a first draft, spend at least one pass looking solely for places you named universal emotions. Chances are they’re spots where you can swap in more vivid writing to spice up your characters.

Need help with your book? I’m available for manuscript edits, query critiques, and coaching!

For my best advice, check out my online classes, my guide to writing a novel and my guide to publishing a book.

And if you like this post: subscribe to my newsletter!

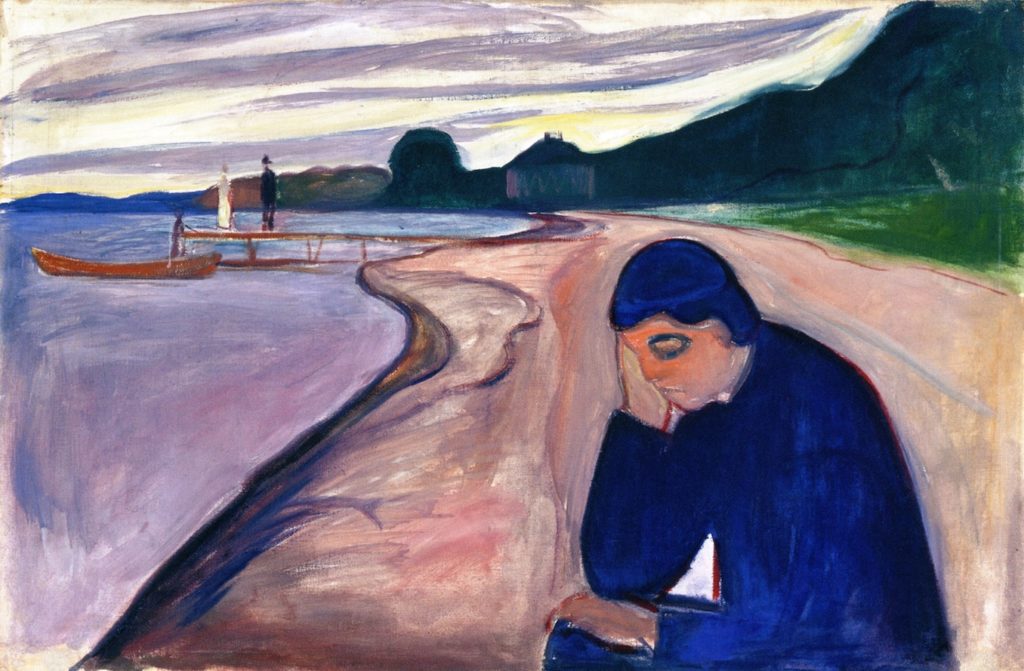

Art: Edvard Munch – Melancholy

I love it when you show and don’t tell, Nathan. Your tutorials have been a great boon to my writing.

Excellent column, as ever. Had to click through from reading via email to give extra kudos for the superb use of #Euro2020 drama in your examples. Correctly stated – on all levels.

But, really, a nineteen year old. 😓

Hey, Alice, cut them both some slack! I’m proud of our whole team, coach included.

Very good advice, some of the examples violate another good piece of advice: Kill the adverbs!

“Alice intentionally kicked her toe on the curb.”

Do we really need “intentionally”? Within this context, I think not.

In another example, there’s one adverb too many. When Alice is thinking in the second sentence, the adverb is fine. We all think sentences/thoughts with adverbs. But do we need “immediately” in the first sentence?

“When she heard the news, Alice immediately blamed the coach. Honestly, who thought letting a nineteen-year-old take the fifth penalty kick was a good idea?”

I’m not criticizing the main point of this blog. I was just surprised by the adverbs. Read Stephen King’s “On Writing.”

I actually disagree about killing all adverbs. In this context, without “intentionally” I worry it might seem like Alice accidentally stubbed her toe? “Immediately” is maybe more discretionary, but I think it conveys a mindset of going straight to the problem.

I agree that adverbs should be used as sparingly as possible and not as a substitute for a better word (e.g. “walked quietly” could be “crept”), but I think the advice can be taken too far.