It’s rare that I disagree with or don’t defer to the experience and wisdom of publishing industry sage Mike Shatzkin, who has been prescient about the transition to e-books and adept at explaining its effects and future effects on the industry.

But in a recent post, he expressed frustration at the failure of recognition on the part of legal experts about the special circumstances of the publishing industry and the potential effects of low e-book pricing:

But I’m afraid my major takeaway was, once again, that the legal experts applying their antitrust theories to the industry don’t understand what they’re monkeying with or what the consequences will be of what they see as their progressive thinking. Steamrollering those luddite denizens of legacy publishing, who just provoke eye-rolling disdain by suggesting there is anything “special” about the ecosystem they’re part of and are trying to preserve, is just part of a clear-eyed understanding of the transitions caused by technology.

The thing is, and I say this as someone who has a great deal of respect for publishers and agents and as a traditionally published author: There isn’t anything special about the publishing industry. It is not deserving of special treatment, and we shouldn’t fear its disruption by new technology.

Books occupy a very central and foundational part of our culture, and any society that stops producing them deserves to get sacked by the Visgoths. Publishers and bookstores have packaged and distributed books to us for several hundred years, and they have been great at their jobs.

But, again, I say this as someone who has tremendous respect for these institutions: They are a means to an end. They are a way of getting quality books to customers, just as stagecoaches transported people across the country before railroad before cars before airlines. Publishers and bookstores are a delivery system.

In order to call for special protection for the traditional publishing ecosystem, you would have to make the case that without that precise ecosystem, books would fail to be produced in the same quality and quantity as they were before. This is Mike Shatzkin’s fear:

My argument and fear is that a restructured ecosystem will deny us books like Walter Isaacson’s Steve Jobs biography or Ron Chernow’s George Washington. Books that take years to write and require hundreds of thousands of dollars of financing to be written will never see the light of day if publishers can’t earn a profit by investing in their creation.

I simply don’t share this fear.

People will still write books even with uncertain prospects for financial success (NaNoWriMo anyone??). There will still be tremendous competition, which will create pressure to make those books as good as possible. Those books will still be delivered to readers, only more cheaply and more efficiently than before. They will still be edited and some will still be great. And better yet, in case I didn’t mention it twenty times before, they will be cheaper, which means customers will be able to buy more of them.

All of the mechanisms and expertise of traditional publishing, other than paper book distribution, are now available to any author. Want professional editors? Tons of great freelance editors are standing by. Need cover design? A graphic designer will be happy to help. Need money in advance to pay for all this? Take a gander at Kickstarter, or at the universities and nonprofits who currently support the publication of literary fiction and academia.

I mean, if Walter Isaacson came to me and said, “Nathan, I have secured exclusive access to Steve Jobs to write his bio, I just need $500,000 to write it in exchange for a share the profits,” I would say, “I don’t have $500,000.” But I’m confident Isaacson would be able to find a member of the 1% willing to take the bet.

What are publishers fighting for? They’re fighting for the ability to charge a premium for their products. To make customers pay more money for books.

It’s a bit galling that the publishing industry would argue that books are more than just commodities, and their ecosystem therefore deserving of special protection, when they are increasingly treating books and authors as, well, commodities. When literary fiction is getting kicked to the curb, when millions of dollars chase the latest celebrity scandal as mid list authors get dumped, and when they’re pulling e-books from libraries.

We have plenty to fear from an Amazonian monopoly, were that to ever come to pass. But there is competition in the marketplace already and there is also tremendous opportunity for upstarts to continue to shake up the landscape.

I have tons of sympathy for all of the great people who will get caught in the negative effects of the disruption. I don’t think publishers will go away, but they will certainly be leaner, which means job losses. I also don’t blame publishers for their actions or even think they’re necessary misguided. They are all very intelligent and well-meaning people who are usually making rational decisions to protect their business in a rapidly shifting landscape.

But when you boil everything down and remove all the noise, the precise fear of publishers is that books will be cheaper. That’s it.

Books. Cheaper.

Tell me again why we should fight that?

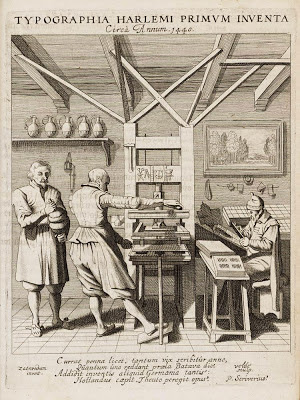

Art: 1628 version of Haarlem printing press from 1440 by Jan Van de Velde

I agree with you.

Exactly. Reading a book should be something anyone can do. It shouldn't require a device, which means we ought to have both print and ebook available.

Publishers need to rethink their positions in the form of partnerships with authors, flexibility is what makes some industries survive and some die a slow death. Books will endure, regardless.

I really like your comparison to transportation and traditional publication being perhaps like the old stagecoaches.

Oh, boy, do I ever agree! No business has any special right to exist. If they serve the customer (and their suppliers) well, they will thrive. If not, if they fail to adapt to a changing marketplace, that's just the free market system at work.

Wow, Nathan. Mega-bravo!!

Brilliant post. Great clarity of thought.

The irony is that if Publishers stopped treating authors and books as commodities, and they started understanding you can make more money pricing lower and selling at higher volumes, they would acheive their

goals, and be much more likely to weather the storm of technological transition.

Slow clap.

Great post, hopefully your brand of thinking will spread.

Yes, yes, and yes.

Great post! I agree a well.

Wish you were still agenting, Nathan. You are fearless and wise. Agents are fearless (they have to be) but they aren't all as wise as you.

As you so rightly point out, ONWARDS.

Funny. I posted this comment on a different blog today, and it is equally apt here, verbatim: Well argued. You always know an industry is at risk when they turn to protectionism to legislate or litigate success rather than adjust to market pressures.

You are 100% correct. Publishing is not special.

The example of "Book X might not be written in the hypothetical future" is specious. One might ask the converse hypothetical question: "What incredible books did not get published in the past because they did not fit in the channels that served the publishing industry?" The original argument presupposes that the publishing industry is perfect today, or at least that whatever harm it does is outweighed by the good it does. There is no way to prove that, and in fact there are solid arguments (made in this blog post!) that point to the opposite.

Noticed recently vs. the 'before times': the tone of agents and publishers to budding authors (me) in query/book proposal mode, is noticeably more generous and considerate of MY time and effort committed to not only years devoted to producing my best work possible, but also to dedicating and educating myself to the understandably competitive requirements of the literary world and profession. Said approach albeit necessary, could -at times- be said to resemble the court protocols of Louis the XIIII; Now thanks to the increasing legitimacy of online publishing and the recent P&RH merger, a much needed re-evaluation of the necessities of each side of the business can flower. To Quote Martha: "it's a good thing".

So agree Nathan. This is a great post. Loved the analogy to stagecoaches. It's so true that the industry has to grow with the times.

Ironically, your example of Walter Isaacson finding a wealthy patron to sponsor a Steve Jobs bio is the way publishing worked before there were publishing companies. Back then, an author would find one or more rich people to underwrite the production of some number of copies of the book he'd written, and in return they'd get copies.

Read the fawning introductions in some 18th-Century non-fiction books singing the praises of someone long lost to history, and you're probably reading an author's suck-up tribute to his "publisher."

Nathan, I've always liked you. Now I like you more.

There are so many quotable lines in this piece, I want to share them all with everyone I know.

This is a good post. Books do need to be cheaper. I buy my books on Kindle mostly but when I do decide to purchase a physical book, I'm usually bothered by the high price.

Now that I think about it—I guess I'm like the inverse of the people who think ebook pricing is too high.

yes, but it's not just about money — it's also about culture, and the dumbing down of the collective unconscious by removing the "gatekeepers", the agents and the editors and the publishers, who, whilst making money, also have, hopefully, an eye for quality and who would, I suspect, not accept a majority of self-published books because they are rubbish. I don't want to read badly written books — I don't care how cheap it was to download. Books should be expensive; not prohibitively expensive, but I think they should cost enough for one to consider them a luxury item, to revere them, and treasure them, to acknowledge the toil invested within those pages. I don't want books to become acrylic — I want my books to be cashmere.

Sam, you might notice that some products today are acrylic yet cashmere is still accessible to those who prefer it.

Last I looked, the textile industry was not given special protections to ensure the availability of cashmere.

Just sayin'.

There are some well reasoned arguments here… but also a huge loss of credibility by comparing the vomiting onto the page that is NaNoWriMo with actual books.

It's nice for self published "authors" that they can come to your blog, and so many others, and know they'll get to hear all the things they want to hear.

The fact that so many people type words then say they wrote a book and describe themselves as authors is undoubtedly driving down the quality of books in general, and the only people who disagree are those who are doing that, or gaining something from it.

Excellent post, Nathan, and I like your comment Peter Dudley.

Nathan, I'm glad you pointed out how the publishing industry is increasingly treating the work produced by writers as a commodity. I've seen quite a few writer friends produce fabulous manuscripts, but they can't get them published b/c there are no vampires, werewolves or zombies (I'm talking about YA). These well-crafted "quiet" books are unable to find a home. As you pointed out, in the age of the celebrity book, the arguments set forth in favor of special treatment are disingenuous.

If J.K.Rowling decided to write another Harry Potter book, we'd all buy it and likely I'd pay $20+ for it. Why? Because we want it. Just like with all products, some are worth more than others. Cashmere and nylon. Mercedes and Ford. A coffee from Starbucks versus the swill at your local Circle K.

I see no reason for books to be any different.

But here's the rub. If publishers want to continue to obtain $15, $20 or more for a book, they are going to have to make that book worth the price and give a reader reason to spend that versus downloading a book for 99 cents (or free) from an Indie author. That $15+ hardcover better have great editing, a fabulous cover, quality pages inside – the whole package better be top notch.

I'm not seeing this. I'm seeing quality -overall – going way down, while the prices are the same or going up.

Big publishing should focus on what they can do best – when they set their mind to it: Produce quality books and charge a fair price.

Do books really need to be cheaper? There are so many books already available for free (at libraries, or online) or for pennies (rummage sales, used bookstores, or online).

One unintended consequence of books being cheaper could be that they'll lose their value. (Sam Albion touched on this, though Peter Dudley has a nice counter; maybe there will still be a range of prices for a range of books.)

The publishing industry doesn't deserve special protections, but like any business, they will try everything to save themselves. This is an industry that never had a high profit margin to begin with, and they're threatened with having products that they used to sell for $20 now having a price point of $2.

They've all seen what has happened to the music industry, and I'm sure it's their biggest nightmare.

I think the publishers are just working our emotions and the historical attachment we, as humans, have to books. They're milking that for all it's worth and saying, "Don't you want to preserve thousands of years of historical significance? Do you want to be the cause of the collapse of something so venerated?" But in reality, anything we humans truly value has proven remarkably tenacious and capable in whatever form is best its survival. We love books. Books won't die just because there is a new way to get them to market. Maybe those traditionally responsible for delivery will die, but not the product itself. That's what the publishers fear, at least the big ones. The new pubs are much more nimble and quick to evolve.

Anon 7 p.m.

You said:

"…but like any business, they will try everything to save themselves"

Yes, but what they did was commit a felony criminal action to try to keep prices low. And the article Nathan references defends that felony. It calls for 'Special Protection' for Publishers, saying they should be allowed to break the law, because they perform a necessary and important function.

If I can paraphrase him – hopefully correctly – Nathan's point is that the function Publishers provide is necessary, but others can and do provide it. Publishers do not deserve exemption from the law because they are not irreplacable. The reality is that they are replaceable.

When people are in competition to provide a service, the market should decide who wins.

Very well said, Nathan. For any industry, if your business model no longer works, change it or go out of business. Only those who adapt to a changing environment deserve to survive.

Books. Cheaper. Why fight it?

Well, as a reader, I wouldn't, but as a writer, I have some concerns. Within the current publishing system, a smaller cover price means the author makes less money.

Unless, of course, the author goes indie and snags a higher percentage of a smaller cover price, which can preserve income. But if indies lose their price advantage because the traditional publishers are charging less, the indies may sell fewer copies, reinforcing the problem for authors to make a living.

Great post, Nathan. I also agree with you. This past weekend I attend and spoke at the Avondale Writers Conference (just outside Phoenix,) and the keynote speech was given by Gordon Warnock, senior agent for the Andrea Hurst Literary Agency. In his speech he said that those who viewed change in publishing with pessimism did so because they're focusing on how things used to be. Those who are excited about the current state of the publishing industry feel that way because they're looking at how things are now and how they could be in the future. I think your post tonight falls right in line with that same line of thought, and traditional publishers are just going to have to get used to it.

YES! (And as Forrest Gump says, "That's all I have to say about that.")

One of your best posts ever!

I applaud your take on the publishing industry and its future – that it should be prepared to adapt rather than continue down well-worn paths of yore. I wonder, though, if in the push to price commodity cheaply as possible, will less risks be taken with publishing choices. Will publishers choose more often to go with trends and low-risk publishing options like celebrity books and biographies than risk publishing dollars on a worthy work that's left of field and which might, or might not, sell well.

I agree, too, that people will still write books even though decades pass in the journey to their completion. It's the journey that, in retrospect, is the most pleasurable for the author. I believe Tolkien took twelve years to write his saga, and I've taken longer to write mine.

On reflection, though, I suppose mainstream publishers have always tried to stick to the tried and true to one degree or another, and the big break-throughs have come when those with risky literary ventures have self-published like Lord Byron his work of epic poetry which, I guess, wasn't expected to become as popular as it did. I wonder if the work was helped by the charisma of the author who probaby held many public readings in order to make his public aware of both his work and his name.

But I digress.

Excellent post.

I really can't see why publishing should have special protections (just like I still can't understand why baseball has their special protection as well). Survival of the fittest.

If you can't change with the times to make yourself leaner and meanter, and more importantly, relevant (see the newspaper industry on how not to make yourself relevant), then you have no one to blame for your own obtuseness except yourself.

One argument that traditional publishers keep bringing up is this idea that the publishers were ‘gatekeepers’ or guardians of literary quality, that the reader needs them to be protected from bad books. The question is actually asked, “with the wave of indie publishing, how will we know what’s good?” Ironically, most submissions editors have told me that they know within the first paragraph if a book is good.

Big six publishers have access to high dollar editors, top graphic talent, massive distribution infrastructure, sales reps, years of experience, etc. but it is all wasted when they use their resources to publish books by empty-headed, vacuous, reality TV stars that have nothing intelligent to say. I don’t know that they have done anything more for America’s intellect that TV, radio or any other medium of pop culture.

I think it's Visigoths, with two Is.

I totally agree with this… with respect to fiction. Fiction can be written for free, and excellent fiction produced at no (substantial) cost to the author. But certain non-fiction (the research required to write it) does usually cost money.

It's why I got into fiction. I wanted to write narrative non-fiction, along the lines of Bill Bryson (as a familiar example) or Pete Dunne (a favourite author of mine) – studies of a subject that were part informative, part memoir/travelogue. The problem? I don't make much. I can pay my bills every month but there's pretty much nothing left over to be able to spend – especially with no guarantee of publication/return! – on travel.

Without that advance up front, there's no way for me to write these books. I don't actually have the platform/pub record to get the advance anyway (learning this was what prompted me to try writing fiction – serendipity, as I love it), but for people who do, it may be their only means of covering their costs.

I think we'd suffer a great decline in both the quantity and quality of such non-fiction books if the authors were left to fend for themselves. Not everyone (possibly very few) would be able to secure wealthy sponsors to take a chance on them.

The one thing that always bothered me was that when people spend hundreds of dollars on tablets or dedicated e-readers they expect e-books to be less expensive. And it's a plain and simple fact that e-books are less expensive to release. I've done it and I know from personal experience. So why they think they can get away with charging these ridiculous prices is something I don't get.

But I also think that as long as the big publishers charge these prices they only make it easier for smaller e-presses and indie authors who are pricing their e-books competitively. I have passed on more than one e-book by large publishers just because they are over the line and I've purchased quality books from small presses instead.

As for the Steve Jobs book. Of course that would have been published. I've read that book, and it was practically put together by Jobs and his wife before he died. It was a great book, but there were no surprises.

You're right, of course. But my question is: Why does it take hundreds of thousands of dollars to develop any book? Writers who demand those kinds of advances will find themselves left out of a competitive, realistic industry.

Bravo! No industry is any more deserving of protection than another! If we "rescue" the traditional publishing houses, then who or what is next? And who bails them out? Government (taxpayers)? The government is in worse shape than publishers.

The free market, with a minimum of regulations, always tends to produce the best product at an affordable price.

The publishers need to learn to adapt like all other industries.

Years ago color TV's, cell phones, VCR's (remember those?) cost hundreds of dollars more but now are far more affordable for the average American…

"There's a moment when Jacob goes inside to warm up some corndogs (natch), and the narrative stays with the kids outside." Great example to the approach.

If anything, when it comes to any kind of protection, real publishing companies – as opposed to accounting entries for multi-media conglomerates might POSSIBLY be in the running.

Companies who actually pay taxes for the streets they use, hire locally and support their host communities, and don't allow their executives to have offshore accounts… MAYBE.

Tariffs, protective legislation, and financial assistance should only apply to the health of the company regarding maintenance of community integrity.

@Seabrooke – maybe it's time to rein in some of ridiculous litigation around defamation and libel.

I don't want to comment on the issue as a whole, rather leave some thoughts about what Nathan envisions as alternative futures/realities for the evolution of publishing (or rather, the adaptations in its absence). I think it's important to consider that there could be such a thing as devolution–that not everything will be advanced as evolution of an industry.

"All of the mechanisms and expertise of traditional publishing, other than paper book distribution, are now available to any author. Want professional editors? Tons of great freelance editors are standing by. Need cover design? A graphic designer will be happy to help. Need money in advance to pay for all this? Take a gander at Kickstarter, or at the universities and nonprofits who currently support the publication of literary fiction and academia."

This paragraph in particular made me think of this. While freelance offers lots of people the autonomy it desires, it heaps a lot more costs on the back of the worker him/herself. In other industries, you would hear the decrying of the rise of contractual labor, in which companies are restructuring their workforce so they are free of responsibility. A freelance editor has to hustle jobs, pay for their own benefits (which often means less of them), and live paycheck to paycheck. A freelancer, is in effect, a single business and in seeking business success, every project can be a career-effecting. Will freelance editors shy away from literary risks in order to take safer projects? Also, where do successful editors come from? I would wager many of them gained their experience through traditional publishing. If becoming an editor means taking on increasing costs to oneself (along with increasing risk), then we should consider how the demographic of would-be editors will narrow socially and economically as a result.

Kickstarter? Academic Presses? Do you think people are going to kickstarter intellectual literary classics? Or Zombie/Vampire/pop-lit? (No preference for either, but you're surrendering to the whim of the masses–if you can stand out of an already saturated kickstarter pool, to appeal to increasingly cash-strapped, donation-weary clientele. As for academic presses–where do you think their money comes from, and what is the mission statement of the presses? Do academic presses have extra room on their lists they've been reserving all this time? I'm not saying these are bad ideas, but as the only systems to prop up an industry–are we going from stage-coach to train? Is that the most proper metaphor? Or would this be more like going train to plane, or train to bus? I don't think it's very clear that these mechanisms (by themselves at least), are necessarily positive, effective, or anymore sustainable than the publishing industry in its current form…

As for this:

"I mean, if Walter Isaacson came to me and said, "Nathan, I have secured exclusive access to Steve Jobs to write his bio, I just need $500,000 to write it in exchange for a share the profits," I would say, "I don't have $500,000." But I'm confident Isaacson would be able to find a member of the 1% willing to take the bet."

This seems like an endorsement of feudal-era patronage. Is this really advisable? Does this adhere to journalistic principles? What if the member of the 1% is an enemy of the biographee? Etc. etc.

At face value, I don't disagree that "publishing is not special," but I just wanted to raise some concerns about some of the mentioned alternatives. I don't believe the freelancification/guerrilization of industry is necessarily a good thing for ALL parties. Sure, the consumer will likely benefit in cost, as they do from all cheapening products, but let's consider the true cost of that cheapening: labor, benefits, wealth stratification. Perhaps the analyst is right: Publishing is NOT special, and perhaps lots of industries need protection from the extreme pursuit of the bottom line.

I do NOT agree with you. As someone who works in the academic publishing industry, I know, for a fact, that you could not be more wrong.

Academic publishers are struggling due to re-sale and ebooks. It takes years to publish a book, as you mentioned, and companies cannot keep up with the rapid changes in technology. A new droid/ipad every year with system upgrades to boot? Typically, when a system has changed, we then have to offer a "fix" to our ebook products, as they will not work. Thus, angry customers. So, we work to fix the problem on the new edition, which will come out in 3-5 years. No matter though, five more ipads will have come out in the meantime.

Yes, a publishing company may need $500,000 to publish one book. But that's to account for the author's demands (grants, resources to write, travel to promote, etc. And if they originally signed a contract in 1989, and their book is on its 8th edition — they earn more money), reviews (reviews are done pre-revision, first draft, art manuscript (if needed), final stages), gratis copies, cover (depends on how much detail/artwork (consumers love artwork, as sales show), digital products (all of our customers say, "students need digital supplements. they don't want a book without digital supplements.")

I recently went to a show where I surveyed undergrad and grad students. 9 out of 10 said that they never want to be forced to have their products only accessible on an ereader. They want the physical book. However, they want the digital option. Guess what? It is more expensive to produce a digital book/supplement than it is to produce a book.

Books would be a hell of a lot cheaper if you couldn't buy used books. the used market is killing the publishing industry. not ebooks.

cassielynn-

Know for a fact that I'm wrong about what? I don't understand how what you're saying relates to my post. Mine is about the trade market rather than the academic market, but even still I'm not even sure which part you're disagreeing with.

Making books cheaper means more accessibility to readers. More accessibility means more sales for them. They have nothing to complain about!