It’s one of the oldest writing “rules” in the book, and probably dates back to the time they were carving stories on stone tablets: Show don’t tell. You hear this all the time. Here’s what “show don’t tell” means.

UPDATED 5/30/19

What show don’t tell means

With the understanding that “if it works it works,” and there are always exceptions, in general: universal emotions should not be “told.”

It’s not interesting to be told that Brad is sad or Mary is merry.

Instead, we should be shown how the character is reacting to their feelings.

We should see Brad crying or Merry jumping for joy.

Why we find reactions interesting

I’m of the opinion that we read books in order to get to know our fellow humans better. We are empathetic animals and are able to put ourselves in the shoes of characters, and thus, we have a pretty keen idea how we’d be feeling in any given situation the characters find themselves in.

And emotions are universal: we all feel sad, angry, happy, emotional, etc. etc. But how we react to those emotions are completely and infinitely different. That’s what we find interesting when we’re reading books and it’s what show don’t tell means.

Being told that a character is “angry” is not very interesting. We’re reading the book, we know his dog just got kicked, of course he’s angry! It’s redundant to be told that the character is “angry.”

More interesting is how the character reacts to seeing his dog kicked. Does he hold it in and tap his foot slowly? Explode? Clench his fists?

Even if it’s a first person narrative and the character knows he’s “angry,” it’s more interesting for the character to describe how he’s feeling or what he’s thinking rather than saying, “I was so angry!”

Other applications of show don’t tell

This also applies to:

- Physical descriptions – It’s not interesting to merely hear that someone is “pretty.” What characteristics make them pretty?

- Characterizing relationships – It’s not interesting to only hear that two people are “close.” How are they close? What do they do together?

- A character’s thoughts – Rather than diagnosing your characters, show them teasing things out and being more vague with their thinking, just like a regular human being.

Basically, whenever describing something, especially something universal: specificity wins. That’s what show don’t tell means.

Need help with your book? I’m available for manuscript edits, query critiques, and coaching!

For my best advice, check out my online classes, my guide to writing a novel and my guide to publishing a book.

And if you like this post: subscribe to my newsletter!

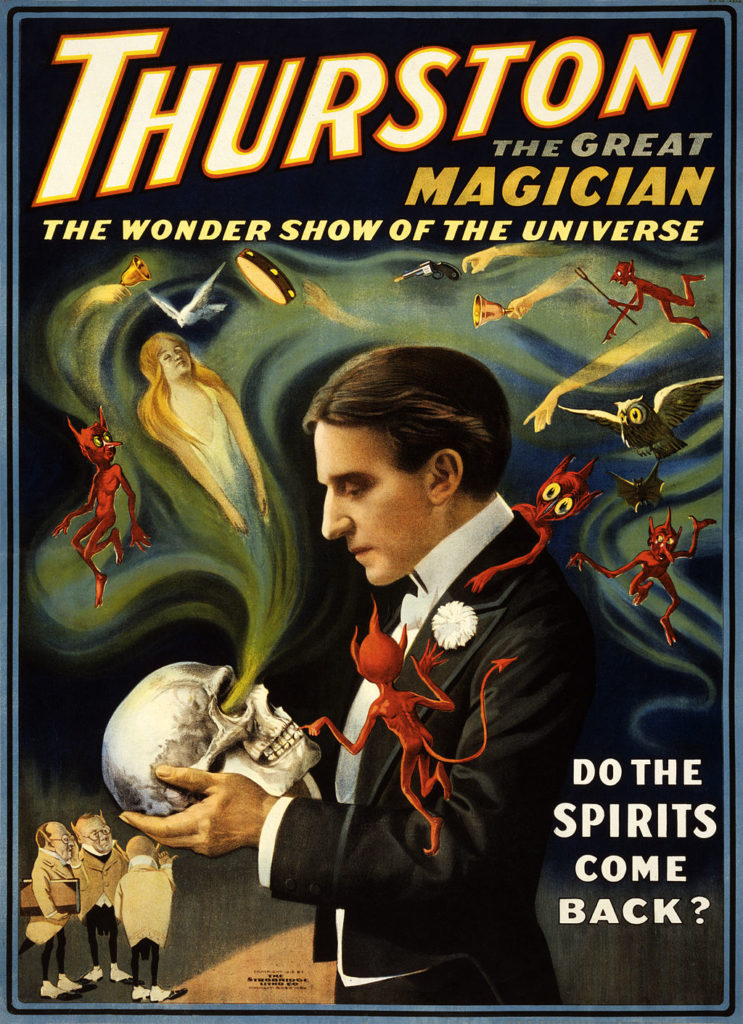

Art: Thurston the great magician

We must be on the same wave length because I mentioned "Show don't tell" on my blog today.

I struggle with showing things the same way…. too many clenched jaws and fists, wide eyes, and sighs.

I try to mix it up, but it can be difficult. I think its cool when writers use unique ways of showing.

For example, one of my favorites:

J.K. Rowling- "Hermione stares daggers at Ron."

Ink —

Thanks. 🙂

The problem with just showing when it comes to emotions is that people show their emotions differently. Take anger. Some people really do slam doors. Some people burst into tears. Some people are self-contained and don't betray their emotions through an action — not even through a subtle gesture. Some people yell. Some people are quiet. Some people bite their lip. Some people hit things (or other people).

Now, to make it more difficult — some people slam doors, but not because they're angry. Maybe they're like my brothers, and just like the sound.

Some people burst into tears — but not because they're angry. They're sad, they're happy, they're confused, they're frustrated. Or maybe their contacts are irritating their eyes.

Some people yell, but not because they're angry. Some people are quiet, but not because they're angry. Some people bite their lip, but not because they're angry.

Heck, even hitting someone isn't necessarily a sign of anger. In sports, if you slug your teammate, it's most likely because he's just done something really awesome, like score a touchdown.

And who knows, just by looking at them, what self-contained people are feeling? They resist demonstration of any sort.

So if you have a drama queen as a protagonist, sure, it's easy to show what she's feeling by what she does. Otherwise, you'll need a healthy mix of telling and showing.

Some people say you should be able to tell from the context of the scene, but you can't. Not always. Not until you really, really know a character, and you just don't know a character that well in the first 20 pages of a book without some telling. (Margaret Mitchell tells us Scarlett is charming before we see Scarlett say a word.) When you're just being introduced to a character, you don't know that the very sound of Oklahoma's fight song will send him into a livid rage. So the first time he hears it, the narrator is going to have to explain his reaction to the reader.

To me, the danger of telling isn't redundancy. At least, not usually. The real danger of telling is being unable to back up what you've told. Margaret Mitchell gets away with telling us that Scarlett is charming, because for the next thousand pages of the book, we see Scarlett's ability to charm. But it would've been much harder to understand Scarlett in that opening scene with the Tarleton twins if we weren't first told, by the narrator, that Scarlett is a charming young woman.

So you want the Kings to show you how they're going to turn around the franchise, not just tell you how they plan on doing it, eh? 😉

I actually struggle with the opposite problem. I'm terrified of telling. I've struggled so hard to curtail every line of telling from my writing, that knowing when it's okay to use it evades me.

For example, transitions between scenes or the rapid exchange of information that telling does.

So Nathan, how do you know when it's okay to tell? When is it actually better?

Patty,

Interesting again.

And I'd agree, for the most part, though I think there are a lot more tricks up the writer's sleeve than the physical actions of characters to convey emotion. Dialogue and actions are the most overt, but there's mood, setting, diction, sentence structure, composition… Cormac McCarthy, for example, often has very spare dialogue, and rarely goes inside the heads of his characters. And he's often spare with physical details, too… and yet his characters are often clear and vivid. The emotion is saturated in the text itself, in the choice of words, the atmosphere, the structure of a clipped or rambling sentence.

I do think redundancy is a problem, at times, with telling… but I also agree with your idea about backing up claims. I've read stories like that, and always thought of it as the Hype Problem, where characters fail to live up to their own hype, fail to live up to their own description within the novel. A tell (even a good one) usually has to be backed up by a good show.

Hey, doesn anyone else but me feel like going back to kindegarten? I just picked up a smoking Bumblebee Transformer for show and tell…

Mira,

Nathan specifically applied what he was saying to descriptions. Direct quote: "It's not interesting to hear that someone is 'pretty' – what characteristics make them pretty?"

As a reader, I disagree. Yes, I want to know that Scarlett O'Hara has black hair, green eyes, and magnolia-white skin. I also want to know what the narrator thinks of her appearance — "arresting," not "beautiful." Because only that gives me a complete picture of Scarlett in my mind — the telling AND the showing. I now see, in my mind's eye, a pale, black-haired young lady who is attractive, not beautiful. It's easy for me to picture her.

It's not easy for me to picture someone the narrator says is "pretty" when there are no details provided. But it's not easy for me to picture a pale, black-haired young lady, either, if I'm not given some kind of value judgment about her features. Do they look well together, or don't they? Because there are plenty of pale, black-haired young ladies out there who aren't attractive.

As you say, it's impossible to describe things without some telling. And I like description. Authors can certainly go overboard with it (see: Victor Hugo, and his 50+ pages about the Parisian sewer system during the climax of Les Miserables), but these days, I see a lot more of the opposite problem. Authors won't describe places or people. And I hate that, because it makes it hard to imagine the story.

People are visual creatures. We like to see things. (There's a reason television is so popular.) If an author can't make me see their story, I just can't get into it. No matter how elegant the prose or how clever the plot.

I see what Patty is saying. I think the problem in my post was that I meant it's not interesting to *only* hear that someone is "pretty" and leave it at that. I didn't mean that we shouldn't hear whether they're pretty or not entirely. I'm going to adjust the post slightly to make this clearer. But I think we're all pretty much in agreement.

Hey Bane

Late to the ball, but …

menace is more menacing when you're wondering why Jimmy is fingering his knife – does he plan to take dog abuse to the next level or is he a darker form of Dark Avenger?

Knowing, in that instant, would be … less.

This element of writing was my steep learning curve, this year.

I find that I want to tell in the prologue and then when the novel begins, I want to show.

I am still learning.(I am always learning.)

So what do you think?

@ Laura 12.59 – …"the concept of "show, don't tell" is truly the BANE of my existence – hardest concept for me to master."

Laura, being aware is half the battle won. You are winning. But I agree with you. I think this is actually much harder than many people realise. Everyone KNOWS what it is, but to really do it well and subtley, is hard work.

I find it helps to listen, and I do mean listen carefully, to the dialogue in TV soaps. They tend to information dump and tell, so as to get much more back info into short time span. Totally spoilt a recent episode of O.C. California for myself listening too hard. It was quite painful. But if I don't pay too much attention, it works.

I think that's sometimes the trick with writing it. One can get so hung up on the writing "how-to's" and what to avoid, that we can forget just to write a darn good story.

Ink,

I agree that there are lots of ways to convey what a character is feeling — and that's why I hate writing "rules." (Something I think all book lovers — agents, editors, writers, and readers — agree on.) I hate "show, don't tell" most of all, because I think it's caused writers to go light on the description, and I like vivid description.

Also, I think "show, don't tell" obscures two important considerations. First: pacing. Showing takes a lot longer than telling. If I need the readers to know that John has a broken ankle, but the details of how he broke his ankle don't matter to the overall story, I don't need to include a scene about how John broke his ankle. A sentence or two should suffice.

Second: rhythm. Language has a rhythm, just like music. Sometimes an adverb, like "quietly," just sounds better than three sentences about a character's tone of voice and mannerisms. There are few things more annoying to me, as a reader, than to have an intense dialogue broken up by sentences about how this character or that character is shifting his legs and wiping his brow. Just say "nervously." I know what you mean. Trust me.

If, on the other hand, what a character is doing is important — if there's a reason I need to know that he's shifting his legs, other than that he's nervous — then show it. And that, I think, is the appropriate line between showing and telling. The more important something is, the more important showing becomes. It's really a matter of emphasis.

Nathan —

Yes, I misinterpreted what you wrote there. Sorry. :)But it's nice that you've taken the time to clarify what you mean when you say "show, don't tell." Half the problem with rules is that it's not always clear what they mean.

Sometimes you tell, sometimes you show. Don't waste space showing things about one-off characters or backstory events. Unfolding plot events should generally be shown. "Attractive, but not a supermodel" might sufficient for some characters, while a full anatomical rundown may be warranted for others. Depends. There are no rules, but you should be aware when you are in either "tell" or "show" mode.

I think anon makes a good point about throwaway characters – if you describe them in too much detail and make them overly memorable the reader is going to wonder why they never come back.

I think the rule that showing is important means that only telling is the real problem. If you write something like: "Mary was angry, but she was also beautiful. John was mesmerized by the young woman’s beauty, but mystified by her anger. As he pondered the situation, the doorbell rang." the reader is soon yawning and putting the book down. This sample has no mood, no description, nothing but the telling of facts. It’s boring. The best writing includes lots of tools: descriptive language, symbols, archetypes, alliteration, etc. that allow a story to work its way into the hearts and minds of readers and make it easy for them to willingly suspend their disbelief in the writer's fictional world.

I’m currently reading THE HISTORIAN by Elizabeth Kostova. I’m enthralled by Kostova’s tremendous skill at balancing the telling of huge amounts of factual information with the most exquisite description.

This is my first time here. 🙂 Wonderful post! I've read so many different articles on this same topic, but I'm forever hoping to read more and (hopefully) learn a thing or two! 🙂

Awesome post today and everyone's comments have been really helpful. This is an area I struggle with, but you've explained it well. Perfect timing too as I'm just sitting down to do some more editing.

Thanks Nathan 🙂

Great tips here. You could guest at The Blood Red Pencil blog. 🙂

Once had a writing instructor tell the class to avoid writing "I feel" or "he felt". Every time we use the word "felt" we are telling and not showing.

patty said:

"People are visual creatures. We like to see things. (There's a reason television is so popular.) If an author can't make me see their story, I just can't get into it. No matter how elegant the prose or how clever the plot."

I agree with you. With so many modern visual entertainment forms (high def TV, cable TV, movies, YouTube films, etc.), we’re more prone than ever to want visual descriptions in our books. The visual aspects of settings in books are as important as the use of stormy clouds and thunderstorms in horror movies. The setting – including weather, buildings, local customs, etc. – can be used as additional ways to make the reader feel what’s going on within the characters. I love to write fiction set in places that have mystical elements within the culture, e.g. Mexico of the Mayans, ancient Egypt, Heian Period Japan. The geographical setting and culture can be used to reflect what’s going on inside the characters.

I love this blog/I finally have community. To color is to show/a detail which pinpoints the idea/a kind of etherial essence of the character. As last week we filled our inboxes filled with e-maqils about 4o'clock anon, I kept feeling that my 3:45pm comment spawned the debacle. Wow am I good.

Thanks so much for clarifing that up for me. It totally makes sence now!

So I was reading through my book (and im a huge movie fan) and I notice that especially in the fight scenes I show alot!

I'm a little worried that I show too much and that it is too much like watching a movie, only you are reading about it. So I'm worried that the scene could either get lost in translation or the reader would get bored.

I thought Jeff Gerke had a great take on the show vs. tell debate here, including his section, "When Exposition Works."

One of my favorite books on the writing craft is Naomi Epel's The Observation Deck. I love this quote from her section, "Get Specific": "Don’t tell us the man got angry; show him punching a hole through the motel wall or biting through his lower lip. Don’t tell us the war was brutal, do as Richard Price suggests: show us the burnt socks of children lying by the side of the road."

Marilyn, I read History: A Novel years ago and it blew me away. Usually I love to look out the window at takeoff when I'm flying, but I was reading the Morante on the plane and was so engrossed in the story that I didn't even realize the plane was moving. Missed takeoff entirely.

AM –

Thank you!

This is one of the best explanations I've heard of this. Will be copying and pasting this post to save. Thanks!

Speaking of old-fashioned books vs. modern visual entertainment, here’s the hilarious book trailer for SENSE AND SENSIBILITY AND SEA MONSTERS: on YouTube.

I think we tell, instead of show when we're being lazy. I feel like that's a big part of it for myself.

Patty,

That's interesting, because I've been known *cough cough* to like description myself, but I usually find that the "tell" is the worst offender in regards to its lack. The tell is quicker, as you say, and often skimps on the description, avoiding the immersion of the sentences, the experiential details that form good description. I find telling is often a shortcut. It's easier than trying to show something, to get inside an experience.

And yes, there's times you don't want a whole scene for something. You don't want a whole scene showing how someone was injured if the how is irrelevant… except I think in the end it often comes back not to the fact that they showed this, but that they didn't show it well. I find a lot of writers will do just what you said… write a whole scene to convey one piece of information, and this sort of showing is usually overkill. It gives too much importance to something that isn't particularly relevant. But the problem, I think, is not the showing, it's the poor use of it. If you show the injury as a sidenote in a scene that accomplishes five other important things… suddenly the scene is alive, it's human and full of vivid experience. You have a complex human reality rather than a stage-set bit of dramatic pedagogy.

So I guess I just think, for both showing and telling, you have to be careful not to discount the whole technique when it is merely the mediocre application of the technique that's the culprit. I think it often comes down to a matter of subtlety. "John was angry" is not subtle. Neither is "John punched the wall." Too much of either to explicate the emotional reality of characters is going to be tiresome. But if you can provide the almost ephemeral and passing details, the little things that we absorb off the page just as we absorb them in real life (almost unconsciously), then we might have an evocative and complex reality.

Okay, have to go watch Princess Bride now.

Marilyn – thanks for sharing bits of your story; I love the description. Especially the last part of this sentence "drawing in the last rays of moonlight before the illuminated slice dipped behind darkened clouds."

Brilliant!

Re: showing vs. telling – I think learning to show comes from experience. The more we write, the better we get at showing. And telling and keeping the pace the quick takes the most skill of all.

Thanks for this. I've never heard it explained better.

i think there's a little more to this issue than the points nathan covered. one of them is trusting the reader. it pays to show and not tell because readers like to be able to deduce things from the text without being told explicitly. the reader deduces that the dog-owner is angry from his physical reaction; telling him or her explicitly is, in essence, patronising. in turn, allowing the reader to make these deductions allows them to engage more with the characters. it's distancing to have a character's psychological/emotional life spelled out all the time. on the other hand, one of the joys of the written word (as opposed to film, for example) is that it has room for precisely that. all things in moderation.

The "show don't tell" mantra is an overgeneralization used for Creative Writing 101 initiates. The reality is that 'showing' is a technique, and 'telling' is a technique, and to create a successful novel you're going to need to utilize both of these (and many others) effectively.

One reason many novelists have trouble with the various "short forms" involved in marketing a novel–the hook, the the blurb, the dreaded synopsis–is that they've focused so much on 'showing' during the actual novel(and a novel is dominated by the 'show', not the 'tell', though there will be some measure of 'telling' in there, too), that they've never mastered the art of telling. A good synopsis simply tells you what the story is about, without too much flare.

So there is an art to telling as well as showing. To end up with your book on the shelves, you've got to learn to balance them both.

~The Anonymizer

I just read your blog, and as I'm judging a bunch of contest entries, it was a timely blog. I just got in, so I haven't weeded through all the comments. I hope I'm not repeating something. I have run across a lot of she smiled. I've been commenting in the entries, "There are a million ways to say someone smiled rather than just telling us she smiled. Be creative. The same goes for she blushed." Well, I'm a bit more tactful. LOL!

JM

Steph Damore –

Thanks so much!!

Has anyone here read HOUSE OF LEAVES by Mark Z. Danielewski, or any other experimental novels of that sort where the pages themselves are arranged to create visceral responses in the reader? Danielewski was a film student who decided to write a book with visual cues, and decided that he would never allow the book to be made into a movie because he wanted the book alone to accomplish the visual experience. I read it, and loved this novel – one of my absolutely favorite books!

I'm with those who think there's a place for telling and a place for showing. A story that is 100% showing could get mighty long and mighty confusing.

I also think it depends on the type of book you're writing – for example, I think the ratio of show to tell would be different in a thriller than it would be in a fictional memoir type story.

A friend of mine deals with couples facing diseases like cancer and dementia. She says she can tell so much more about a married couple by their body language than from what they say.

One husband let his wife, who was battling terminal cancer, go alone into a session. He said he'd wait out in the hall because "he had work to do on his laptop".

My friend said as this couple left the building the husband walked way ahead of his wife and didn't hold the door for her. It told my friend so much than anything he could have said about their relationship.

Show don't tell is action and not words.

To me, a lot of this issue is bound up with POV. You need to "show" what your POV character experiences. "Telling" in that sense can be okay as well, because the way your MC "tells" also shows you who he/she is. Thus the unreliable narrator, who is filtering events according to his/her perceptions of them.

I tend to favor pretty close POV, so your mileage may vary here. It's interesting to look at how far away we've gotten from the omniscient narration that was pretty standard not so long ago.

The POV thing is always interesting in that the telling and showing in any story is through the filter of the narrator/MC's POV. I like to begin stories with an omniscient POV and then draw closer to the MC during the first chaper.It's interesting to show the shory world and MC from this all-seeing, unbiased view and then become privy to the thoughts of the person the reader has been following.

I think showing and telling together is usually a bad idea. It's usually redundant.

To be informed that a female character is "pretty" and that she has "blue eyes" is yawn-producing.

Which brings up another point: the quality of the showing.

FYI, showing doesn't have to be long-winded; it can be concentrated by use of figurative language, metaphor or simile, for example. Besides, it's not the quantity of detail but the quality. One killer detail is all you need sometimes.

Other Lisa said:

"It's interesting to look at how far away we've gotten from the omniscient narration that was pretty standard not so long ago."

I started thinking about the same thing last night, as a result of the discussion here. I came up with a couple of theories about why fiction evolved from omniscient narration to highly visual description.

One reason might be that, because computers make it so much easier for everyone to write and publish books today, we have more competition and more excellent books than ever before. In the past, limited numbers of people with access to printing presses might have resulted in people capable of writing even better books never having written them. Also, with the difficulty inherent in making changes to a manuscript prior to computers, books of the past were probably not edited for actual content as well as they might have been. Despite badly written books that get published today, I think that, overall, literature is published with a much higher standard than ever before.

Another reason might be that older books emerged out of a tradition of oral storytelling in which the storyteller provided the visual entertainment: facial expressions and so on. Maybe, when people read, they pictured an imaginary storyteller. Today, we’re so used to movies and television, we want to forget the storyteller and step directly into the scenes we’re reading about.

The first writing course I took in college, the teacher kept hammering "show don't tell" but didn't explain it very well. He was a good writer, and has since become very successful, but wasn't that great of a teacher.

Anyways, I took this mantra to mean that you can't tell plot elements, and had to show the person crossing the room, opening the door, walking outside, etc. So of course I got poor marks on my assignments.

As a result, I hated the class, hated writing, and gave up out of frustration for more than a decade. I still have a hard time getting over my fear of "telling" anything at all.

Personally, I really enjoy the third person omniscient point of view. Perhaps because in movies and television you rely so heavily on visual effects and can't really get inside the characters' heads.

To me, 3rd omniscient is "real" literature. I get such pleasure out of knowing how all the characters respond differently to a situation, even though they don't say so out loud. It's what makes reading a book different from any other form of storytelling.

But that's just me.

Nathan, I've been thinking a lot about your poll last week, regarding when people write.

I was wondering if you would consider doing another poll, regarding other responsibilities we have.

I was thinking of something like this:

– Work full time (non-writing)

– Work part time (non-writing)

– Full time parent/caregiver

– Full-time writer (earning most of your income from writing)

– Part-time writer (part of your income from writing)/part-time other job

– Part time writer (no other job)

– Part time writer/part-time parent or caregiver

– On sabbatical to write full-time

– Other

I should probably add one more category – full-time parent/caregiver who also earns some income from writing

Anonymous,

Obviously, I don't think calling a character "pretty" and "blue-eyed" is yawn-inducing, and (outside of poetry) I hate most figurative language. There is nothing worse to me than a forced simile, and most similes are forced.

Simple, lucid, straightforward. That's the kind of writing I like.

And that just goes to show why writing "rules" are absurd. People like different things. If you don't like "pretty" and "blue-eyed," you probably didn't care much for Harry Potter. J.K. Rowling described most of her characters, even the minor ones, in loving detail. And she's a billionaire. Which means a heck of a lot of people like the way she writes.

Christine H,

I love 3rd person omniscient, too. I also like 3rd person close. I'm not a huge fan of first person.

I hate present tense.

But I love, love, love The Hunger Games and Catching Fire, both written in first person, present tense.

Which just goes to show — there are many, many good ways to write, and we can love something that we think we'll hate, and that's why writing rules are so stupid. They encourage conformity in an area that, by its very nature, is vibrantly chaotic.

Thank you for this excellent post, Nathan. This is the best explanation and examples I have seen on show don't tell.

I'm new to writing with hopes of becoming published and have had trouble with this issue. I think it is something that, to a certain extent, needs to be relegated to that first rewrite. For me it got to where I was feeling bound to a chair, unable to move or write because I was so worried about telling.

Be aware of it, but don't let it cripple your initial efforts; then let your editor point out the scenes that need work.

To add my two cents to the comments of others – I also enjoy omniscient POV and find it is my default POV when first coming up with a story.

Sandra

Thank you for the post. I still have the trouble with show, don't tell, especially because editors sometimes go all over the place. For example, at a resent conference an editor said that it was not enough to say that a character slumped his shoulders. When I asked more what I should do, they went into walking aways sad. I'm a little confused. Is slumping your shoulders right?

Thank you.

Anon 8:36 – good examples.

The thing you have to understand about the "rules" of strong writing as that adherence to them is probably necessary, but insufficient to guarantee that your work will be readable and ultimately publishable.

"Show, Don't Tell" is a lesson in how to make a brick, and your objective in writing a story is to build a skyscraper.

For example, here is an example of "telling" something:

The attractive woman walked across the lobby.

This contains very little information. You don't know much about the woman, or about what is going to happen. There's nothing that frames this as an important event. If this is a background detail, you may want to describe it this way, but it's a fairly bland way to introduce a character

Now here is the same event with a lot of "showing":

The sound of Jimmy Choos clicking against imported Italian marble echoed through the cavernous space as the twenty-six year-old woman crossed the lobby. Her hair was shoulder-length and medium auburn, cut fashionably, and it accented the amber flecks in her emerald-green eyes, which were the first feature most people noticed about her, unless they were more drawn to her ample C-cup breasts or her tan, shapely legs.

There are a lot of details here, but they're not quality details. The color of her hair and her eyes don't tell me much about her, nor do the anatomical descriptions. The showing here is aimless and pointless and ultimately ineffective.

People's eyes probably need to be described for some kinds of romance, and their bodies probably need to be described in erotic stuff, but generally, showing on its own is only a rudimentary first step before you figure out what you're going to show, which is what makes it a story. This kind of description is bad because it doesn't advance the narrative. I think this isn't significantly better than the first example, which had brevity going for it.

Here's something I think is more effective:

Beads of cold sweat rose on the back of his neck as she approached, and the sharp noise of her heels against the marble floor of the lobby seemed to him like the ticking of some terrible clock. He smiled at her and stammered a greeting, and she purred an acknowledgement. Her mouth was red and sensuous, with just a little bit of cruelty in the corners of it, and he thought, when ruined men trace back their lives to figure out where it all got away from them, they probably end up at a moment like this, with a woman like her.

Now, here, the condition of her being attractive has been converted into plot; somebody being attracted to her. Rather than describing her entirely, we've seized on a couple of key details, her mouth and the sound of her high heels against the floor. A single evocative detail contributes a lot to the reader's visualization and advances the character.

Think about a boxer's broken nose; the bridge is crooked and one side of it is flattened, and when you've got that nose, the reader will extrapolate the face it fits into.

Think about prominent gums, and lips peeling back off of them when a character smiles. Think about receding chins. Think about a stain on a shirt collar, a stubbly spot the character missed when he shaved. Think about damp handshakes and dirt under fingernails.

Have a perspective character notice these details and use them to frame the relationships. Think about how this stuff fits into the conflict in the scene and the narrative.

Mastery of the tools is the first step, but you're not really there until you employ those tools for some overarching purpose.

Daniel —

To be honest, I liked the first example best. I really couldn't care less if someone's high heels are clicking against the floor, and I've certainly never thought clicking heels sounded like a "terrible ticking clock". To me, that kind of detail sounds forced and melodramatic. I'd throw down a book that included it in a second. I like a fast pace, and figurative language like that slows down a scene way too much for me.

You obviously like something different. So we're different. And there's room in the market for different types of storytelling. Not everyone writes the same way; not everyone likes the same style. There is no one kind of good writing.

One of the more common mistakes, I think, is to try to show EVERYTHING. You don't have to do that.

Show the IMPORTANT things.

You can describe a place or person in a few well-chosen words.

If you spend three paragraphs on something, that better be absolutely crucial to the story. If not, you're wasting the reader's time. Just get on with it. Save the in-depth descriptions for what really counts.

Just my humble opinion.