One of the most interesting things about novels is the extent to which the very thing a novel is about — a quest — is also the thing that best describes the writing of the novel itself.

Our characters go on a quest. We go on a quest to tell their story.

Our characters struggle. We struggle. Our characters strive. We strive.

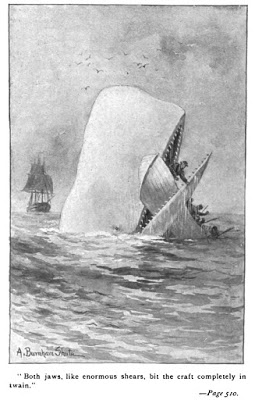

This is one reason Moby-Dick is my favorite novel. It’s truly an insane novel. Meandering, strange, packed full of things that don’t belong, filled with moments of brilliance and stretches of tedium. What better living metaphor to the writing process than a psychotic chase for a white whale who may or may not exist, has already taken its adversary’s leg, and who most likely wants him dead?

And, similarly, I’ve already written about how the striving of Jay Gatsby in The Great Gatsby is best understood as a writer’s own wish that the world would conform to our wishes rather than what exists in front of us.

So naturally I was drawn to an article in Quartz yesterday about the secret to happiness: always wanting and pursuing more.

Science, take it away!

Neuroscientist Jaak Panskepp argues that of seven core instincts in the human brain (anger, fear, panic-grief, maternal care, pleasure/lust, play, and seeking), seeking is the most important… It can also explain why, if rats are given access to a lever that causes them to receive an electric shock, they will repeatedly electrocute themselves.

Panskepp notes in his book, Affective Neuroscience, that the rats do not seem to find electrocution pleasurable. “Self-stimulating animals look excessively excited, even crazed, when they worked for this kind of stimulation,” he writes. Instead of being driven by any reward, he argues, the rats were motivated by the need to seek itself.

Yes, you read that right. When rats are given a means of shocking themselves, they will go ahead and do that even though it’s completely unpleasurable.

The quest to explore our surroundings and boundaries is powerful. So is the drive to tell the story. And explore still more in the process.

Need help with your book? I’m available for manuscript edits, query critiques, and coaching!

For my best advice, check out my online classes, my guide to writing a novel and my guide to publishing a book.

And if you like this post: subscribe to my newsletter!

Art: Illustration from an early edition of Moby-Dick by A. Burnham Shute

Admin, if not okay please remove!

Our facebook group “selfless” is spending this month spreading awareness on prostate cancer & research with a custom t-shirt design. Purchase proceeds will go to cancer.org, as listed on the shirt and shirt design.

http://www.teespring.com/prostate-cancer-research

Thanks

Heads up Nathan. "This is one reason Moby-Dick is my favorite novels."

Excellent post! People are interesting–and apparently, so are rats. Keep seeking and chasing dreams! I will! 🙂

'And, similarly, I've already written about how the striving of Jay Gatsby in The Great Gatsby is best understood as a writer's own wish that the world would conform to our wishes rather than what exists in front of us.'

Nathan, that's one of the truest things ever written. All my novels – including those for children – have been about wish-fulfillment – that is, the fulfilling of how I'd like my life to be. These days, I'm a little bit more about how I wish the world could be for others given there's so much suffering. With that in mind, I now write stories with ideas – gleaned from my 62 years on this physical plane while delving into spiritual realities that affect this one – that might inspire others to have better lives. I would love it if they could.

We are taught in high school English classes that there are some basic themes in literature, and, in addition to a "quest," they involve an inherent conflict:

Man vs Man

Man vs Nature

Man vs Himself.

In many ways, the "quest" is the last: man versus himself. The quest is either improvement or destruction; like the rats in your science study.

I was a few years ago enlightened to another conflict, which in a way could be a sub-set quest of Man vs Himself: man versus angels, or demons; in the first instance, against his more base nature, man (or woman) is forced to be better, to improve, to be more compassionate, more understanding, more forgiving; in the second, it is essentially an inherently "good" person struggling against demons that seek to draw him down to his basest level.

What form the "enlightenment" took was an analysis of Hemingway's "The Sun Also Rises," essentially a seemingly anti-status-quo, rebellious and rejecting tome about how the world had changed the young after World War I, how religion and morals etc had no place in the modern world. The analysis described Jake Barnes, Jacob, as not an "we're all fucked" sort of depressing story, but rather, as Jacob wrestling the Angel: a religious, biblical allegory.

In other words, even as far back as the beginning of religions, let alone religious stories, allegories, and the writing of fiction or even 'histories,' the conflicts of mankind have been clear to writers, perhaps because they have inside them the same opposing ideas or forces, and are struggling, through writing, to defeat or join whichever side within them is the most powerful.

And, by so doing, explain to readers at large a way, a path, to a resolution of the conflict, whether positive or negative, uplifting or depressing. If depressing, I'd suggest, then the path of the quest in the story is meant to demonstrate the way to NOT follow; if uplifting, a way that could bring the reader light at the end of the tunnel.

In that way, as a writer, I believe it is our duty, perhaps even our calling, if not merely obsession, to try and reflect the conflicts existing for millenia in our world or even just our perception of it, and to try and demonstrate a path followed on whatever quest the character embarks, the quest being a resolution to the conflicts taught us at early ages. Hemingway wrote once, in Death in the Afternoon, a fictitious character–"the old woman"–asked him about writing when he was writing about bullfighting, and particularly she wanted to know: why do you always write about death? Why do you always have characters die in your stories and novels?

To which he responded, again, fictitiously, as the woman was a device for writing what he wanted to write: "because that is how all stories, if told truly, end." Becuase that is how we all end: in death.

There is tragedy even in the most uplifting of stories or quests: the tragedy is in knowing, as with Hemingway's own death, that no matter how well written a story or described and resolved a conflict, there is one quest a writer essentially embarks on that the writer will never know if they succeeded at: immortality.

The real quest of mankind–to find a way to NOT die, to find a way to continue, despite all the conflicts, to live, to write, to think and to feel.

We are all rats, to be sure. But even knowing we'll be electrocuted if we touch the lever, we take the risk. Because. Someone has to be the first, or the second, or at least one of those who braved it and lived to…write about it.

Thanks, as always, for a thoughtful post, Mr. Former Agent Man.

Those rats sound like the people who are first down the stairs in horror movies. Especially if they go back for me. But I'll admit, questing and seeking and plain old curiosity drives me in a lot of ways. It probably has a large part in me being a pantser.

Very interesting article Nathan. And I have to agree with you, as I personally write it's like I am experiencing the exact same thing as my characters. When I killed off a character once in my story, I had to stop and cry myself.

I believe it is our duty, perhaps even our calling, if not merely obsession, to try and reflect the conflicts existing for millenia in our world or even just our perception of it, and to try and demonstrate a path followed on whatever quest the character embarks, the quest being a resolution to the conflicts taught us at early ages. (Glassesshop.com)