room in Kensington, Brooklyn for three months. I had an idea for a novel. It

was to be set across two locations – New York and Venice.

The book would follow a young girl, Paige, who dreamt of being a

cartographer. She was best friends with a boy called Sebastian who had

dyslexia. He wanted to build gondolas.

I spent three months “researching” New York, haunting Park Slope coffee

shops and bookstores. I volunteered at the Park Slope Food Co-op, and then

as a magician’s assistant. I ate a lot of organic broccoli from the Food Co-op

but also maxed out on American Pancakes.

One day, I walked straight into Paul Auster outside the Community Bookstore

in Park Slope in which I’d had my first ever taste of Green Tea. I grinned at the

author inanely, and stepped aside.

I didn’t read much (although I did obsess over Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in

Brooklyn, which I borrowed from the Brooklyn Public Library) and I wrote

even less.

In December, I came back to the UK and realised that, while I had a wealth of

ethnographic research and a massive overdraft to boot, I had no book. There

was also no plot, no real sense of who my characters were, nor what made

them tick.

Fast-forward two years and I was now based in London and working in Soho

at a small literary agency. One Friday evening, on my commute home walking

alongside the Thames on the South Bank, it struck me that the canvas I had

chosen was too epic for me to handle. I decided to shrink it, and write an

entirely different book, this time an autobiography.

It would be set in the middle of England where I grew up. My parents had

divorced when I was five, so I was brought up in two family homes, one in a

town called Northampton with my Mum (population 180,000) and, every

other weekend, I was based in a small village with my Dad (population 180).

Over the course of the next year, I drafted 80,000 words. Only then did I

realise the two major shortcomings with this project:

1) Nothing happened to me.

2) Nobody knew who I was.

I consigned the book to live under the bed. It served as quite good sound

insulation.

Aged 32, I moved to rural mid-Wales, with a partner and a three year-old

daughter and a nine month-old son. If I turned my back for more than two

seconds, my crawling baby son would be found fingering plug sockets or head-butting skirting boards.

By the age of three, he’d been hospitalised twice for whacking his prominent

forehead, once having to be put under general anaesthetic in order to stitch

his wound up again.

And it was under these circumstances – when I had been reduced to survival

mode and when my horizons only reached as far as when I could reasonably

consume another cup of strong coffee – that I managed to write the book that

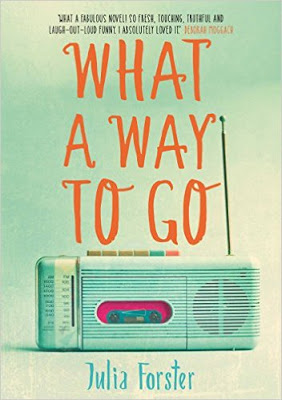

would find its way into print, What a Way to Go.

Can you picture those old-fashioned T-model Fords, the ones which needed a

metal hand-crank to get the engine to fire? You’d put the crank into the front

of the car, engage the ratchets, and then manually heave it round until the

engine stuttered into life.

That was my brain.

My synapses hadn’t fired for that long that to begin with, the connections mis-fired.

For example, you would have thought that in order to commence a novel,

you’d launch Word or Scrivener. Well, I launched the Excel application and

began to compose my novel in tiny little cells on a spreadsheet.

I am not kidding when I say it took me three months to realise the error of my

ways. By that time I was halfway through a six-month writers’ bursary which

had been kindly awarded to me by Literature Wales.

By then, I was caffeine-addled and desperate. Turns out, this was the best

state of mind in which to write.

I completed What a Way to Go over the next 18 months. I wrote as if my life

depended on it, because it turned out that it did.

More about What a Way to Go: It’s 1988. 12-year-old Harper Richardson’s parents are divorced. Her mum got custody of her, the Mini, and five hundred tins of baked beans. Her dad got a mouldering cottage in a Midlands backwater village and default membership of the Lone Rangers single parents’ club. Harper got questionable dress sense, a zest for life, two gerbils, and her Chambers dictionary, and the responsibility of fixing her parents’ broken hearts…

Set against a backdrop of high hairdos and higher interest rates, pop music and puberty, divorce and death, What a Way to Go is a warm, wise and witty tale of one girl tackling the business of growing up while those around her try not to fall apart.

Love the sound of this book. Sympathize with your journey!

Did I miss something? How not to write a novel: Not on an Excel spreadsheet? Oh yeah: Life happened too and got in your way a lot. Happens to all of us.

Yeah, sounds like a perfect imperfect life for an intriguing memoir. That's the way to write a novel. The hard part was and still is getting known. How'd she do that?

Seems like most of us have to learn the hard way how not to write.

Congratulations on the book, Ms. Forster!

Congratulations on the release of your novel, Julia, and achieving such an intriguing story-line. Who needs synapses?

I like her voice. I bet I'll like that book of hers, too.

Thanks for this one, the kind of post I love to read. The gondola making dreams will have to show up somewhere… Let us know.

Julia here – thank you for your comments and again thank you Nathan for hosting. I did, in fact, one time try to be an apprentice to a gondola maker in Venice myself, but was refused, because the only design technology classes I'd ever done were in plastic (I'd only succeeded in making an egg cup).

I think I might pin 'who needs synapses?' above my writing desk…

Interesting! We have broadsheet newspapers, so why not spreadsheet novels?

For a novice writer trying to get her voice heard, what advice would you give for length of book treatments! When I googled this question, I discovered that many blogs suggest 5-10 pages, and, then there is Lena Dunham's now leaked 66 page book treatment!

Can you provide some guidance between sounding too cocky and providing the right sizzle to entice a literary agent? Is it too presumptuous to say you flesh your characters as deeply as J.K. Rowling or your action sequences carry the punch of Lee Child? I've heard two schools of thought: 1. Straight up exactly as requested; 2. Show how you stand out.

The two seem contradictory.