Reader Drew Turney wrote to me recently with an interesting question. There’s so much advice, commentary, and opinion about stripping away anything unessential to a book’s plot. Writing in the modern era emphasizes moving the plot forward at all costs, and everything else is “ruthlessly killed off no matter how darling.” Digressions and detritus that might otherwise be compelling on their own are eliminated.

Is this a purely modern phenomenon? And is it for the best?

My opinion: Yes to both.

Yes, I do think it’s a modern phenomenon. I also think that stripping the unessential is a reflection of the fact that people are getting better at writing books.

But it’s complicated.

We’re living in a golden era

We tend to view the present in a negative light, especially when it comes to books and literature. Today’s books can’t hold a candle to Hemingway’s and Fitzgerald’s, today’s readers aren’t as noble and patient as readers in the 1950s, social media and distraction and e-books are killing literature (even though studies have shown people with e-readers read more).

We always think things are getting worse relative to some golden era in the past.

Partly this is because the only books we read from past eras are the good ones. All the pulp, all the duds, all the forgettable ones have largely been forgotten and have been lost to history. We tend to forget that the classics we read were very rarely the most popular books of their time. Every era had its pulp, its celebrity books, and its, well, crap.

And because we elevate whole eras above our own, we also tend to treat classics as sacred and perfect. We don’t spend much time thinking about how the books from the canon could have been improved upon or how, say, Dickens could been that much better if he had just reined himself in a little.

When you compare a writer like Marcel Proust to a writer like Jonathan Franzen, you can see the way literature has progressed. Both have incredible insight into human nature and a compellingly unique worldview, but Proust’s insights are buried in a tangled mess of digressions, false starts, and drudgery where Franzen’s are delivered in the context of a compelling plot.

We think of books like vegetables. If they don’t taste good they must be good for you. But does consuming good literature really have to be wholly difficult?

Stripping away the unessential is, I would argue, both a product of how books are now written (it’s way easier to strip when you’re writing on a computer or typewriter than when you’re writing by hand), but also because it makes the books better. The modern era has proven that books can be both great and readable.

That’s the point, isn’t it? Can’t meals be both healthy and delicious?

And yet…

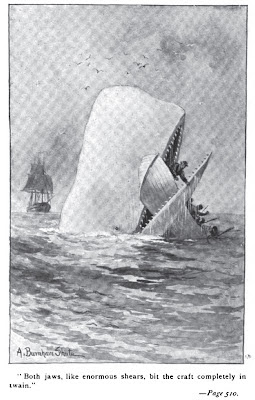

But even still, I have mixed feelings. After all, my favorite book is Moby-Dick precisely because of its scope and its digressions and the sheer insanity of its vision.

Moby-Dick stripped down just to the plot would be about a hundred pages of a crazy captain chasing a white whale. But it’s so much more than that. In Moby-Dick, the unessential is the essential.

There are modern writers who embrace Melvillian levels of digressions and detail (David Foster Wallace springs to mind), but it’s extremely hard to imagine Moby-Dick making it through the modern day editorial process.

As much as I believe we don’t give modern readers enough credit, I do think we’re ultimately less patient with digressions. We’re so bombarded by polish and economic storytelling in books, TV and movies that it can be jarring to sit through something that meanders and takes a while to get to the entertaining bits. I find it really difficult to focus while reading older books.

So in our drive to making things polished and entertaining are we losing moments that are otherwise great on their own? Can economy of storytelling be taken too far?

The power of choice

I still believe that people will look at the beginning of the self-publishing era as the start of a golden period.

For one, there’s now a whole lot more competition. For most of the history of publishing, the vast majority the books were written by a privileged few in small circles. If you weren’t rich, white and knew the right people, good luck. I fail to see how those really can be considered golden eras. Now the process is opening up to everyone, which means more competition and more choice.

There’s also now room in the market for things that the publishing industry wouldn’t have published in earlier eras, which, sure, means a lot of subpar books out there, but it also means that books that are quirky and strange and digressive will also be out there too.

The pressure to sell books and get a publisher drove a lot of literary writers to strive for both literary appeal and readability, and I don’t know that that was necessarily a bad thing. But now the freedom of self-publishing will allow people with a non-mainstream vision to have their work out there too. Books won’t have to be readable in order to find their audience.

So while the modern era of books drove us all to focus on economy and kill our darlings, things may well be changing. Writers won’t have to sacrifice their vision in order to find their readers.

Maybe digressions will make a comeback.

Need help with your book? I’m available for manuscript edits, query critiques, and coaching!

For my best advice, check out my online classes, my guide to writing a novel and my guide to publishing a book.

And if you like this post: subscribe to my newsletter!

Art: Illustration from an early edition of Moby-Dick

It boils down to the question, "What is the point of a novel?" A mystery novel serves a different purpose than a literary novel. Some novels exist to entertain; some to enlighten; some to educate; some to transport. The spectrum is as broad as the population of readers, and as diverse. What qualifies as a digression in one novel may be indispensible to another. As Umberto Eco wrote in the Postscript to The Name of the Rose:

"After reading the manuscript, my friends and editors suggested I abbreviate the first hundred pages, which they found very difficult and demanding. Without thinking twice, I refused, because, as I insisted, if somebody wanted to enter the abbey and live there for seven days, he had to accept the abbey’s own pace. If he could not, he would never manage to read the whole book. Therefore, those first hundred pages are like a penance or an initiation, and if someone does not like them, so much the worse for him. He can stay at the foot of the hill."

I'm a firm believer that the form should fit the function. There is no pace that is one-size-fits-all. Novels are immersive experiences, and like all experiences, some are fast and some are slow. There is nothing to be gained by slashing the slow parts. That would be like trying to watch a movie on fast-forward. Pointless.

If your reader has the attention span of a gnat, so be it. He can stay at the foot of the hill.

One modern author who is both very digressive and very popular is Haruki Murakami. For long-winded writers looking to see how its done, check him out.

Certainly, much of what people view as 'rules' will turn out to be 'trends'.

I look to authors like David Mitchell, who have blended commercial success with quality.

Cloud Atlas is my favorite book and it's quite long–not Moby Dick long by any means, but longer than most books these days.

The most skilled writers can use digression as a tool for character advancement and even plot advancement as well. In Cloud Atlas, sometimes you think three paragraphs were a digression but actually were a critical piece to the story.

As others have said, you have to make the digressions compelling and entertaining, otherwise they kill the pace of the story.

I have no patience for books that are completely processed and stripped down, and that lack any character development. Books like The Da Vinci Code and throw away thrillers never leave you satisfied, except for maybe a cheap thrill here and there.

It's my belief that authors are better off erring on the side of character development even if it means occasionally digressing.

Especially if your in this for a career and not just a get in, get out, make a buck stint.

Ultimately, I think as readers, the authors we repeatedly buy and worship all focus on characters and creating a truly memorable reading experience, and that means having at least a small amount of digression.

There is a segment of mindless people out there that just want to read whatever trash is put in front of them, but I can't in good conscience write for them.

Not to sound like a snob, but we all know what happens when you consume a diet of only candy and junk. I'd rather be Elton John than N Sync.

Yeah, and some of us like those slow foreign films, too. You know, the ones that give us the richer, more thoughtful experiences.

This post reminded me of a website where you can paste a sample of your writing into a window and a computer algorithm grades your writing on a scale of "Fit" to "Flabby". It turns out my narratives seem pretty athletic. I couldn't resist testing some of "The Great Gatsby" which received a strong "Flabby" rating.

https://www.writersdiet.com/wasteline.php

Very nice post and one that made me think. Details are the spices you add to the mix to heighten flavor. I've read a few authors who are too stingy with the deets and are all about plot. That's simply too dull, in my mind.

I like to linger, to take my time, to enjoy the moment (sounds like I might be talking about something else and you wouldn't be far off).

However, there are some classics, like Moby Dick (Herman Melville was my senior seminar thesis in college as an English major), that are rife with details that do add a great deal of flavor, but which nonetheless, feel a bit too nitty-gritty. I know that's a personal taste, so I understand the disagreement.

In the end, I much prefer some digression to none at all — it's what makes life all the more interesting.

Keith

I love that this post somehow, how shall I say this… digresses. You look both backward and forward and take into account changing times and appetites, socio-economic issues past and current and societal norms.

And yet not a word wasted. Good model when it comes down to it.

I had a hard time finishing this post. Way too much digression, far too little vampire love.

No one can say the first chapter of Franzen's Freedom or the whole railroad digression in The Corrections is anything else but drudgery. We've come far, but not that far.

I remember watching a program on a similar topic but in regards to movies. Particularly, the movie, North by Northwest from 1959 was discussed and this aspect stuck with me. Shown was a segment wherein Cary Grant stood on the side of a road looking/waiting for someone and minutes went by as several cars went by. Modern shows and movies leap from frame to frame until we are exhausted. I remember thinking, along a similar line, that the parts of the newer Star Wars movies that were cut were the ones that slowed down and added depth to the characters and their relationships. They were cut in favour of 20 minute action sequences it seemed.

@Chris Phillips – Lol.

Stripping away 'unessentials' is … essential. However, shortening the prose for the sake of simplifying the story, or in an attempt to stick more closely to the plot, without any deviation or embelishment seems to be the popular take on things.

Personally, I'm a little bored with being told our attention spans are minimal, and there's simply no time to wander a little off the beaten track. If the writing style is compelling and enriched with meaning, give me more!

Funny you mentioned David Foster Wallace, since I was thinking about him during the earlier part of your post. I'm about a quarter of the way through Infinite Jest right now, and I feel if you stripped away all the unessential parts, there would be nothing at all left!

My only problem with rules – the people who go nuts enforcing them.

Do I think bloated, neverending sentences are enjoyable? No.

Do I writers should be verbally eviscerated if they try to use an adverb or adjective? No.

In all things, balance is key.

I was a teenager in the 1950s. I'm now 72. So I have what I think is a great perspective of this excellent topic. Yes to people are less patient today, and yes to commenter #1, Steven, who says "I can't helping thinking we're losing something important." Lately I've been going back to Hemingway and Fitzgerald and Faulkner (yes, Faulkner makes you REALLY think). Those earlier great works of literature do force one to sit back, relax, and go with what today's in-general reader thinks is a slow narrative flow. But there is so much beauty, so much of human nature in that flow.

I agree with the premise that prose generally benefits from being concise; clarity should be our watchword. However, this "rule" is not carved in stone, and good prose is predicated on quality, not quantity!

I blogged on this topic using Moby Dick as context–you might find it interesting (even if you disagree): https://bit.ly/NGZEGS. If links are not allowed here, please delete the url. I hope you'll at least give it a read and let me know your thoughts.

Aden

It's definitely possible to strip away the unnecessary while still writing with scope and vision. I'm reading (savoring) Vikram Chandra's Sacred Games, and it's the most incredible experience: over 900 pages long, complex as a spider's web, taking place in four or five or more different eras– and yet it's one of the most engrossing page-turners I've ever read. Not a single thing in it is nonessential. Everything I've read so far (and I'm about a third of the way through) comes back into the plot later on; all of the characters are important, and ever new viewpoint is fresh and timely. (If the next two thirds of this book hold up, I'm going to be raving about it for years.) Cutting away extraneous matter doesn't mean shaving down the book to nothing– it means making room for all the important things you want to put into it.

Basically, I have to completely disagree. Are MOST books better shorter and right to the point? Hell yes.

Would LOTR be the phenomenon it is and the greatest story ever told if it was published today? Hell no.

Love ya, NB, but longer is better when it comes to greatness, in my book.

I agree and disagree. There are digressions today in traditionally published books in the form of elongations of the plot and sometimes unnecessary suspence that leads to nothing. These tend to be moulded by selection and anything that doesn't fit simply doesn't get selected. However digressions of the kind of Moby Dick's might be digging their way through to the readers again slowly but steadily. Self-publishing is the bliss of today's reading industry and although it comes with a lot of disadvantages eventually it will evolve to something more systematic and maybe less hazy.

I have often wondered if someone like Stephen King would be able to get published today if he wasn't… well, Stephen King. Some of his books go on and on before he gets to the point. His books feel like he is telling you the story instead of 'showing' you. I grew up on his writing, loved his writing, but when I tried to get published I was told not to do those things that he does so freely.

I agree, books like Moby Dick in today's world would be cut to bare nothing. I partly blame it on our high-tech society where kids are used to texting, playing video games with awesome graphics, and doing things that are fast and keep their attention. Not many people want a slow read that you ease into anymore. Kind of sad.

Yay! I'm so glad you're a Moby Dick fan. The wonderful thing about his digressions is how utterly essential they are!

Anyway, I agree that the modern world is impatient with digressions, but at the same time, very long books can succeed. Perhaps the publishing industry is actually more impatient with long, digressive stories than readers are. Still, I completely agree that a story should be clean, not lost in floundering descriptions and tangents. It's part of the writer's craft to tell the story he wants to tell and not get distracted from it by his own ideas.